The second portion of a lecture I gave for The Chicago Literary Society on January 16, 2006. You can read the first portion by visiting the blog.

Poetry and Responsibility

At the outset of my remarks I said that I would look more broadly at the subject of poetry and responsibility. For me, that starts with the question of poetry and personal responsibility, then moves to poetry and civic, or public, responsibility.

Robert Frost has secured his place as a major American poet. When I read his poems, as spare and musical and perfect as the classical models from which he learned, I think that no American poet of the 20th century could have worked his material harder. (Frost may have been an indifferent farmer, may have hammered together rude boards for a writing stand, but if you wonder about how hard he worked at his real “work,” just look at the achieved perfection of poems like “The Silken Tent.”.) But dark tales of Frost the man, which we learn from the biographies, make one think again about the work. Frost was heard to say, after the suicide of his son Carol, “My poems are my children.” That’s great for the poems, I thought, but what about the children? It is a step in our loss of innocence to learn that the poems which have given meaning to our lives are sometimes written by people with whom we would not enjoy having dinner. What then of this paradox, as old as art, of great poems written by not-so-great people? The poems after all are still the poems, regardless of who wrote them. In a few generations, when living memory of the author is gone, the work will remain. Readers will return to it or not according to its powers to help them live their own lives. Here is what I have told myself in answer to this conundrum: “Poets, like anyone else, are capable of the best and the worst behavior. The poem is where the poet goes to be the best person he or she can be; to have the world not as it is but as it should be.” But this answer, to be candid, feels improvised, convenient and sophistical.

Here, in translation, is a forward to her poems written by Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

In the terrible years of Yezhovism I spent seventeen months standing in line in front of the Leningrad prisons. One day someone thought he recognized me. Then, a woman with bluish lips who was behind me and to whom my name meant nothing, came out of the torpor to which we were all accustomed and said, softly (for we spoke only in whispers), “ — And that, could you describe that?” And I said, “Yes. I can.” And then a sort of smile slipped across what had been her face.

At a reading a few years ago of a new translation of her poems, someone suggested that she, a better poet than mother, had gone to the prison only once during the seventeen months her son was imprisoned there, even though her preface states otherwise. The least hint of fraud has the most chilling effect on my admiration for a poet’s work. If the poet’s life is completely at odds with the poet’s work, how can the voice in the poem be speaking to us with that utter honesty which is the hallmark of poetry? How do we separate the poet from the poem, the dancer from the dance? In questions of poetry and personal responsibility, we may look into the poet’s heart and still not know the truth — even when the heart in question is our own.

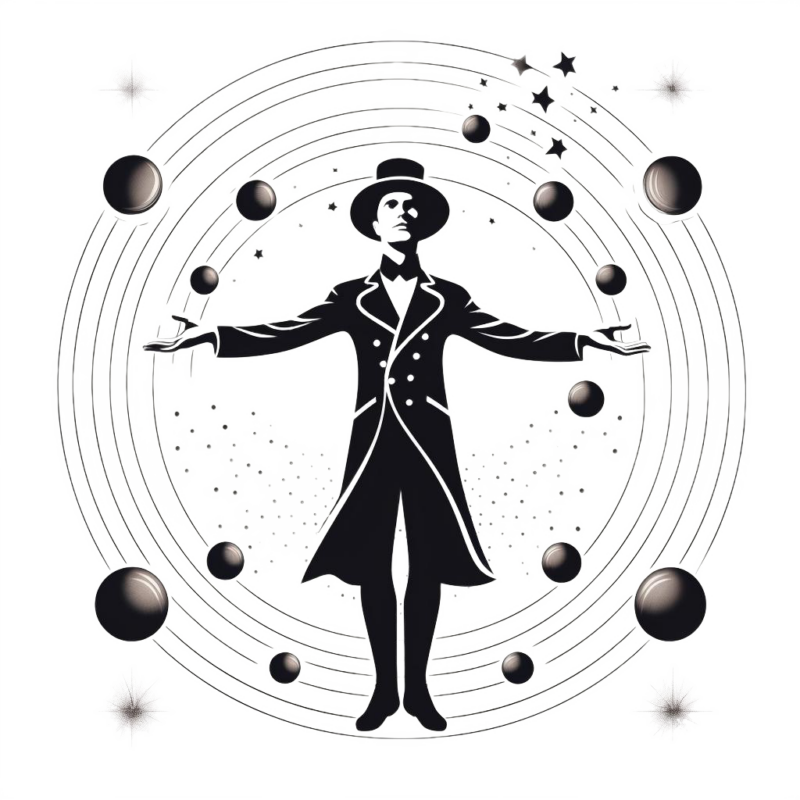

Poetry and public responsibility, on the other hand, can be measured against the world it seeks to influence. Ezra Pound, the P.T. Barnum of Modernism in poetry, began to make his presence felt a century ago. The founder of literary magazines and literary movements (Blast, Imagism, Vorticism); iconoclast writer about writing (Guide to Kulture); early promoter of Joyce, Eliot and Frost, Pound set American poetry on the course it was to follow for the next century. To his own poetry he brought perhaps the finest ear of his time:

From the long boats they have set lights in the water,

The sea’s claw gathers them outward.

Scilla’s dogs snarl at the cliff’s base,

The white teeth gnaw in under the crag,

But in the pale night the small lamps float seaward.

This supremely confident man, who knew what to do and how to go about it in the poetry world, was completely unhinged when it came to the rest of the world. He tried to make poetry do everything, to make poetry the lever that would move the world. (How I admire that!) But what came out was a compost of Fascist rant, anti-Semitic raving and crackpot economic theory. As the years went by and the big literary prizes eluded him in favor of his protégés, Pound’s behavior degenerated from the exuberant to the outrageous to the self-injurious. His wartime radio addresses in support of Mussolini landed him in an Allied prison camp at the end of WW II. In lieu of a treason trial he was committed to the prison ward of St. Elizabeth’s hospital for the insane. Twelve years later, through the intercession of the major American poets of the time (a story in itself), he was released and for the rest of his long life barely spoke or wrote again. Who can know what was in his mind, but to me Pound’s act of silence was the equivalent of Oedipus putting out his own eyes when he saw what he had done.

Ezra Pound is almost a role model for any poet wanting to get completely crosswise with the external world. Contrast this with the career of W.B. Yeats as a public man of his time.

I walk down the long school room questioning;

A kind old nun in a white hood replies;

The children learn to cipher and to sing,

To study reading-books and histories,

To cut and sew, be neat in everything

In the best modern way — the children’s eyes

In momentary wonder stare upon

A sixty-year-old smiling public man.

Pound and Yeats were not contemporaneous in age but they overlapped (the younger Pound served Yeats as personal secretary for a time). The events of Irish independence, culminating in Easter 1916, swept up both Yeats the poet and Yeats the patriot. As a leading Irish literary figure Yeats was a founder of the Irish National Theatre and ran the Abbey Theatre. He suffered the daily trials of any businessman with deadlines to meet, and these fed back into his poetry.

The fascination of what’s difficult

Has dried the sap out of my veins, and rent

Spontaneous joy and natural content

Out of my heart. There’s something ails our colt

That must, as if it had not holy blood

Nor on Olympus leaped from cloud to cloud,

Shiver under the lash, strain, sweat and jolt

As though it dragged road-metal. My curse on plays

That have to be set up in fifty ways,

On the day’s war with every knave and dolt,

Theatre business, management of men.

I swear before the dawn comes round again

I’ll find the stable and pull out the bolt.

The title of the collection containing this poem, published in 1916, was “Responsibilities.” (The epigram for the book, which could serve as epigram for our theme tonight, reads: “In dreams begins responsibility.”) Unlike Pound, Yeats the poet was always able to see how poetry sat with the larger world, as in these lines from “Adam’s Curse.”

‘A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

Better go down upon your marrow-bones

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones

Like an old pauper, in all kinds of weather;

For to articulate sweet sounds together

Is to work harder than all these, and yet

Be thought an idler by the noisy set

Of bankers, schoolmasters, and clergymen

The martyrs call the world.’

Yeats was keenly aware of the demarcation between the worlds of external and internal realities. Frequently his poems record the public man suddenly aware of the poet anguishing within.

Both Pound and Yeats were activists who sought to influence the political events around them, respectively the rise of Fascism and the rise of Irish nationalism, but with opposite personal outcomes. A cynic might say that Pound’s mistake was in choosing the wrong (i.e., losing) side. But the Irish rebellion of Easter 1916 failed as well. I would rather ascribe the success of Yeats and the failure of Pound to their differing views on how one goes about trying to change the world. Pound saw the world at large as an extension of the one he knew, the world of poetry, and spoke to it accordingly. One can only imagine the bureaucrats in Mussolini’s government reading this canto against usury with a view to extracting a usable fiscal policy:

Usura rusteth the chisel

It rusteth the craft and the craftsman

It gnaweth the thread in the loom

None learned to weave gold in her pattern;

Azure hath a canker by usura; cramoisy is unbroidered

Emerald findeth no Memling

Usura slayeth the child in the womb

It stayeth the young man’s courting

It hath brought palsey to bed, lyeth

between the young bride and her bridegroom

CONTRA NATURAM

They have brought whores for Eleusis

Corpses are set to banquet

at behest of usura.

Yeats saw the world of poetry and the world at large as separate and dealt with each on its own terms. He wrote great poems about the events of his day; he used his stature as a leading poet to get involved; he then worked, not as poet but as politician and administrator, to influence those events. Poets before and after these two have tried it both ways. In the Yeatsian model one could name poets as early as Sir Thomas Wyatt and John Milton, and as recent as Archibald McLeish and Vaclav Havel. All of these poets, many of them major poets, influenced the world around them not as poets but through their talents as accomplished men of affairs. In the Poundian model one could name poets as early as William Blake and Percy Shelley, and as recent as Amir Baraka and Poets Against the War. Poets of the Poundian model, up there in their declamatory ozone, tend to write with more certitude but sometimes with less influence than those of the Yeatsian model. When Shelley declared poets “the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” he was claiming the high moral ground for the kind of truth in which poetry deals. But when Amiri Baraka famously or infamously asserted in his 9/11 poem,

Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed

Who told 4000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers

To stay home that day

Why did Sharon stay away?

he was asserting as fact something which the general public would regard as fabrication. The effect was to impair the credibility and reduce the influence of the poem with all but those already inclined to agree with Baraka. In fact “Somebody Blew Up America” is the words of a partisan speaking to partisans. Such poetry rallies the already persuaded by giving voice to their shared passions, but it makes few converts. Nor is that what it intends. This preaching is directed not at the congregation of the undecided but at the choir.

When the sponsors of Poets Against the War opened their website, they were doing so under a kind of continuous dissenters’ rights which is, as we have seen, part of the franchise of modern poetry. If the purpose of public protest is to rally the advocates and to publicize your views, then Poets Against the War exceeded by a country mile the hopes of its founders. It attracted the participation of thousands of poets and coverage by the national news media. Moving beyond the poetry world it became a cultural gathering ground for all those opposing U.S. military action in Iraq. It was the equivalent of those anti-Vietnam demonstrations in the 1960s. No doubt the movement also galvanized those opposing the opposers, who saw in Poets Against the War arrogation on a massive scale and a massive display of adolescence. (The performance of the poets reminded one observer of “lemmings, wilding and Woodstock.”) In itself that indignation probably amused the gadfly-organizers of PAW. But if the aim of public protest is also to influence the course of events by exerting pressure on those in power, then PAW would have to admit failure. The only visible effect of Poets Against the War on the Bush Administration was to postpone indefinitely the reception for poets which had been scheduled at the White House.

Poetry can lend emotional weight to one side or the other of the great issues of its day. (Think of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and its electrifying effect on the passions of the abolitionists in the Civil War.) This power of poetry to sway public debate places a hefty burden of responsibility on the poet. All the more so because poetry does not arise from the kind of logic on which questions of public policy is debated. Its appeal comes not from reason or logic but from the emotional appeal of a point of view memorably expressed. The risk is that the poet’s knowledge of the right course of action will be no better than anyone else’s; if you look at the choices they have made in their personal lives, it may not be as good. A further risk is that poetry written for political ends may not be poetry at all, but propaganda. (As someone said, “Art is an invitation to an idea; propaganda is a call to action.”)

Plato famously placed poetry “on the level of opinion, along with fancy and belief.” He did not regard it as knowledge or truth, and therefore excluded poets from his perfect Republic — at least those poets of the Poundian variety. Yeats, on being asked for a war poem, responded with “On Being Asked for a War Poem.”

I think it better in times like these

A poet’s mouth be silent, for in truth

We have no gift to set a statesman right;

He has had enough of meddling who can please

A young girl in the indolence of her youth,

Or an old man upon a winter’s night.

Yeats, an elected member of the Irish senate, presumably saw in the poet the citizen at the end of the world.