Speech is as natural to human kind as breathing. We inhale, and speech becomes potential, becomes a possible outcome. We exhale. The charge of air, mined of its oxygen, enters an Aeolian wind tunnel. The throat unseals and partakes. Sounding over the harp of the vocal cords, modified by tongue and teeth and lips, the warmed cloud of waste gas enters the room as language. Speech is as natural to our kind as fur to its dog.

Consonants are for communication, meant to be heard by others. But nobody owns the vowels. They are emanations from the animal in us all. They are emotion, raw. As cow to cow, coyote to coyote. In a single gaping yawn, without the use of tongue or teeth, it is possible to sing, yodel or howl the entire medley of vowels: Aa — ee — ii — o — oo. Consonants speak for civilization, but the vowels, sounding, speak for our selves.

Because speech is so effortless, we generate it in copious quantities. Talking to ourselves, thinking out loud: This kind of language is harmless but also nearly specious, like painting a house with water. Yet this dross is also the medium of poetry. This language, shed with our daily breath, hardly worth listening to, is also the clean-burning, high-octane fuel of a poem. It is also the reason why poetry is an event of the ear, not just the reading eye.

A poem is a sound train. Airy aspirates, diphthongs, fricatives, apocopes: Poetry is sound bites indeed. A poem is the shaped whistle of our experience. Whatever language is (I think it happens in the bonding of what is human with all that is not), its use by poetry is paranormal, incantational, even punitive. A poem is a parley with unknown forces. It uses words like talismans to control the refractory material of experience. When Odysseus, trapped by the Cyclops in his cave, was asked his name, the cunning hero replied, “My name is No Man.”

Mss

Since I start things on the margin

— cocktail napkins, cancelled checks,

timetables trying to be reliable —

and since I save it all, I know

there are good words buried and lost

in those fat accordian files, words

that sounded good at the time,

that I promised to get back to,

rhyme trains that never left Grand Central,

monikers that chattered like silverware

at 30,000', sounds struck

sheer of sense — coin of a realm —

from a currency of air, pronounced

like blessings on an express world,

soul puffs, plain mistakes,

angels, working definitions of.

From The Hundred Fathom Curve: New and Collected Poems by John Barr (Red Hen Press, 2018)

Be the first to receive my essays by subscribing to my biweekly newsletter. As thanks for joining, you’ll receive a free PDF of my out-of-print book, Centennial Suite. To read more of my work, please visit my website at johnbarrpoetry.com.

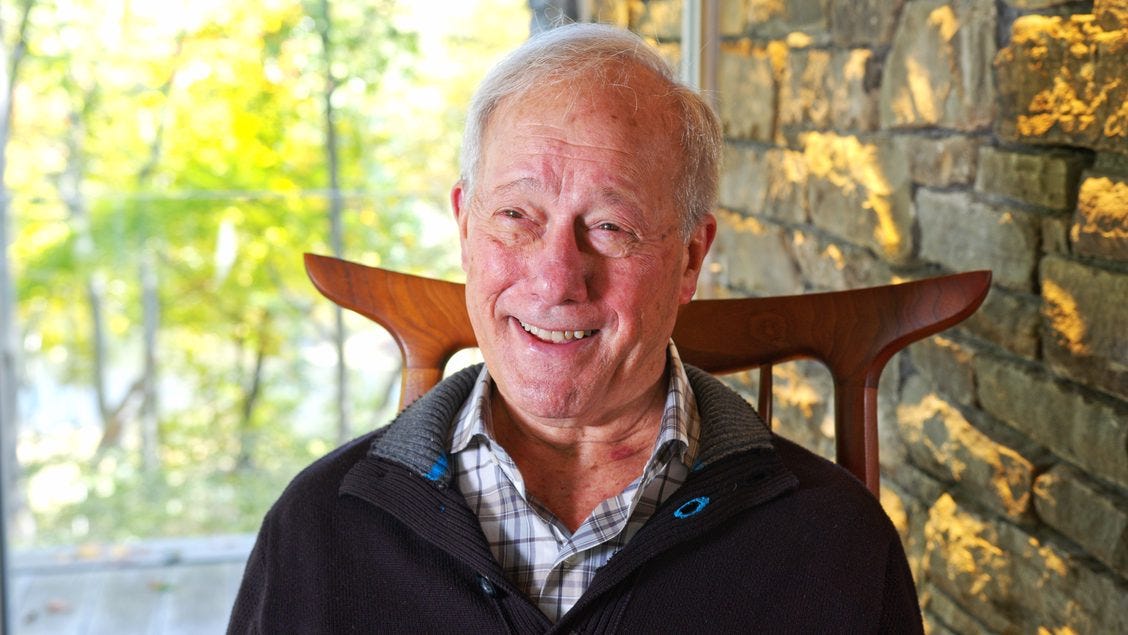

John Barr’s poems have been published in five books, four fine press editions, and many magazines, including The New York Times, Poetry, and others. John was also the Inaugural President of the Poetry Foundation. His newest book, The Boxer of Quirinal, will be published by Red Hen Press in June 2023. You can view more of his work at johnbarrpoetry.com and on Instagram (@johnbarrpoetry).

Latest Posts

Free Newsletter Sign Up

Join over 5 thousand subscribers. Sign up to receive poems and brief thoughts about the state of the art of poetry a couple of times a month for free.

As a welcome gift, I’ll send you my free, digital version of my latest poetry collection, Iron’s Keeping on signup.

Iron’s Keeping is a story in poems that tells of my coming of age as a U.S. Navy officer by going to sea in a voyage that took me around the world. It is of the few published collections of poems about the Naval experience in the Vietnam War.