Is it Poetry or Is it Verse? — Part 2

2.

Efforts to define the difference between poetry and verse (like efforts to define the difference between poetry and prose) have been with us for a long time. Verse is often a term of disparagement in the poetry world, used to dismiss the work of people who want to write poetry but don’t know how. Verse in this usage means unsophisticated or poorly written poetry. But quality of writing is not the real difference between the two. Yes, there is plenty of poorly written verse out there, but there is also plenty of poorly written poetry — and sometimes the verse is the better crafted.

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

The Arctic trails have their secret tales

That would make your blood run cold;

The Northern Lights have seen queer sights,

But the queerest they ever did see

Was that night on the marge of Lake Lebarge

I cremated Sam McGee.

“The Cremation of Sam McGee,” with no help from the critical establishment, is still going strong after a century, while most early Yeats is read today only because it was written by Yeats. To use “verse” as a pejorative term, then, is to lose the use of it as a true distinction.

George Orwell gives us another way to think about this when he describes Kipling as “a good bad poet.”

A good bad poem is a graceful monument to the obvious. It records in memorable form — for verse is a mnemonic device, among other things — some emotion which very nearly every human being can share.

Into this same pot Orwell puts “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” the work of Bret Harte — and presumably “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” “There is a great deal of good bad poetry in English,” says Orwell; by implication there is even more bad bad poetry. My own nominations to the latter include the work of Edgar Guest, whose Collected Poems, in a signed limp leather edition, was one of two books of poetry in the house where I grew up (a wedding present to my parents).

Ma has a dandy little book that’s full of narrow slips,

An’ when she wants to pay a bill a page from it she rips;

She just writes in the dollars and the cents and signs her name

An’ that’s as good as money, though it doesn’t look the same.

Orwell’s distinction, between good bad poetry and just plain bad poetry, is one based on quality of execution, of craftsmanship. Good bad poetry is verse competently — even memorably — written. But his distinction leaves unaddressed the nature of the poem itself.

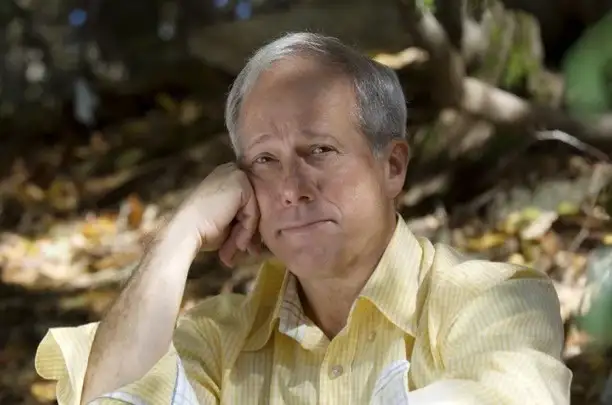

Be the first to receive my essays by subscribing to my biweekly newsletter. As thanks for joining, you’ll receive a free PDF of my out-of-print book, Centennial Suite. To read more of my work, please visit my website at johnbarrpoetry.com.

John Barr’s poems have been published in five books, four fine press editions, and many magazines, including The New York Times, Poetry, and others. John was also the Inaugural President of the Poetry Foundation. His newest book, The Boxer of Quirinal, will be published by Red Hen Press in June 2023. You can view more of his work at johnbarrpoetry.com and on Instagram (@johnbarrpoetry).

Latest Posts

Free Newsletter Sign Up

Join over 5 thousand subscribers. Sign up to receive poems and brief thoughts about the state of the art of poetry a couple of times a month for free.

As a welcome gift, I’ll send you my free, digital version of my latest poetry collection, Iron’s Keeping on signup.

Iron’s Keeping is a story in poems that tells of my coming of age as a U.S. Navy officer by going to sea in a voyage that took me around the world. It is of the few published collections of poems about the Naval experience in the Vietnam War.